The Surprisingly Difficult Problem of Polycube Enumeration

The Inspiration for This Project

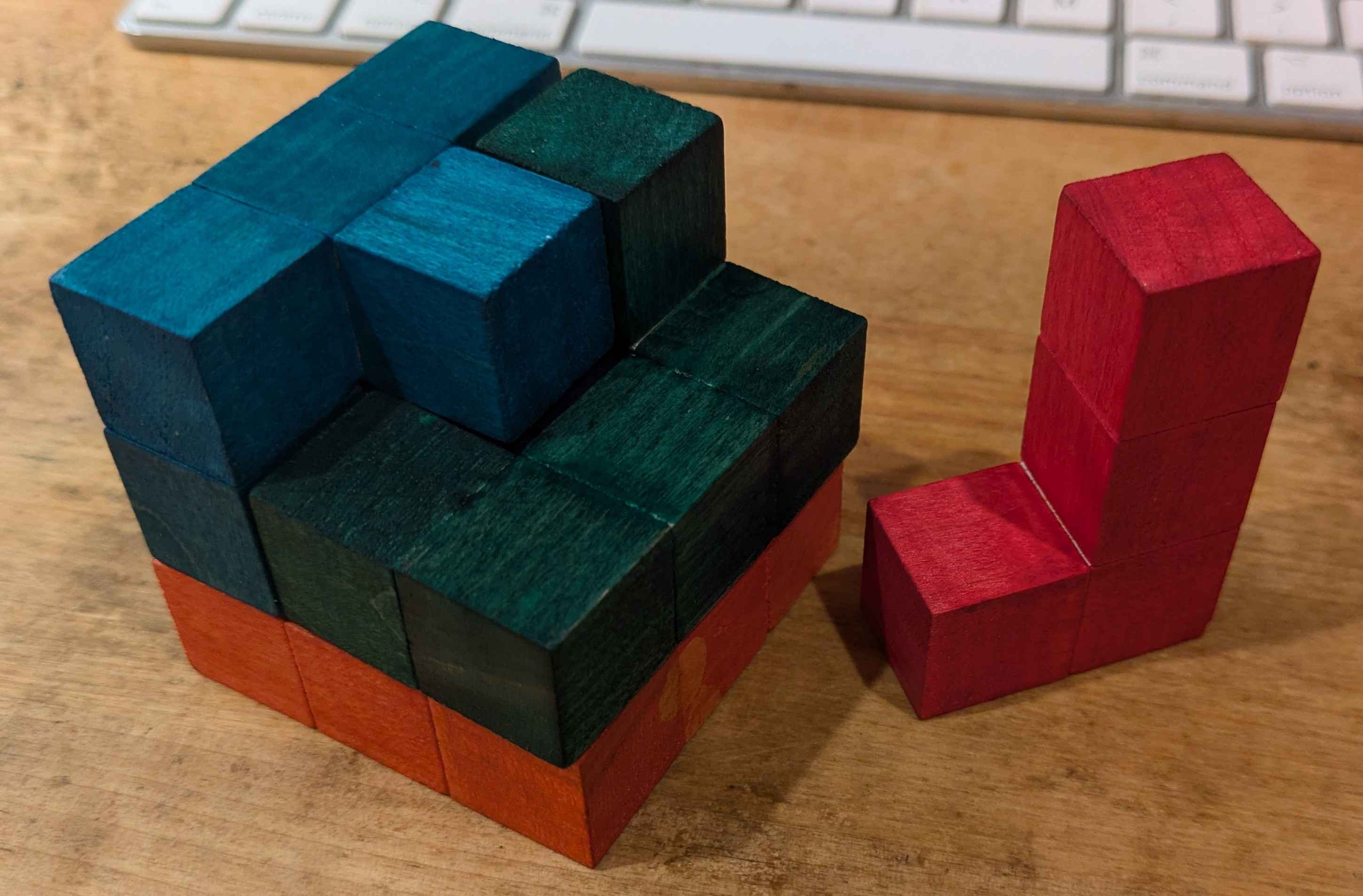

In my Intro to Engineering class, we were tasked with building a Megaron puzzle cube out of 27 3/4” wood cubes. A Megaron cube consists of 5 puzzle piece (each built out of some number of 3/4” wood cubes) that should assemble into a 3x3x3 cube, as shown below:

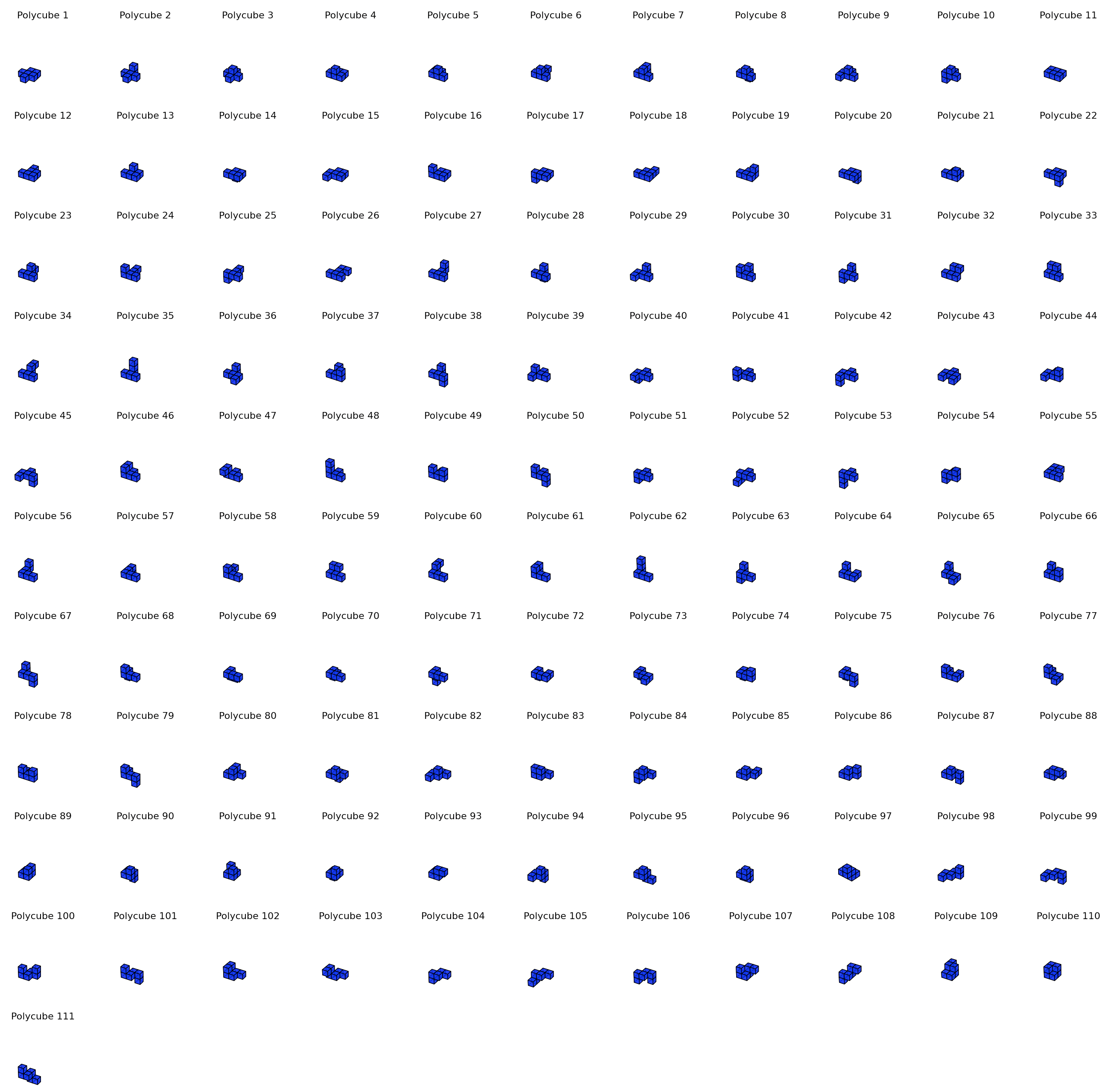

Part of the assignment was calculating the number of unique possible puzzle pieces given n 3/4” wood cubes. There’s 1 possible puzzle part for 1 wood cube (obviously), 1 possible puzzle part for 2 cubes (different orientations still count as the same cube), 2 possibilities for 3 cubes, and 6 possibilities for 4 cubes. It gets a little trickier to keep track of the number of possibilities as n exceeds 5 - I think my teacher underestimated the difficulty of the problem when she assigned it.

Part of the assignment was calculating the number of unique possible puzzle pieces given n 3/4” wood cubes. There’s 1 possible puzzle part for 1 wood cube (obviously), 1 possible puzzle part for 2 cubes (different orientations still count as the same cube), 2 possibilities for 3 cubes, and 6 possibilities for 4 cubes. It gets a little trickier to keep track of the number of possibilities as n exceeds 5 - I think my teacher underestimated the difficulty of the problem when she assigned it.

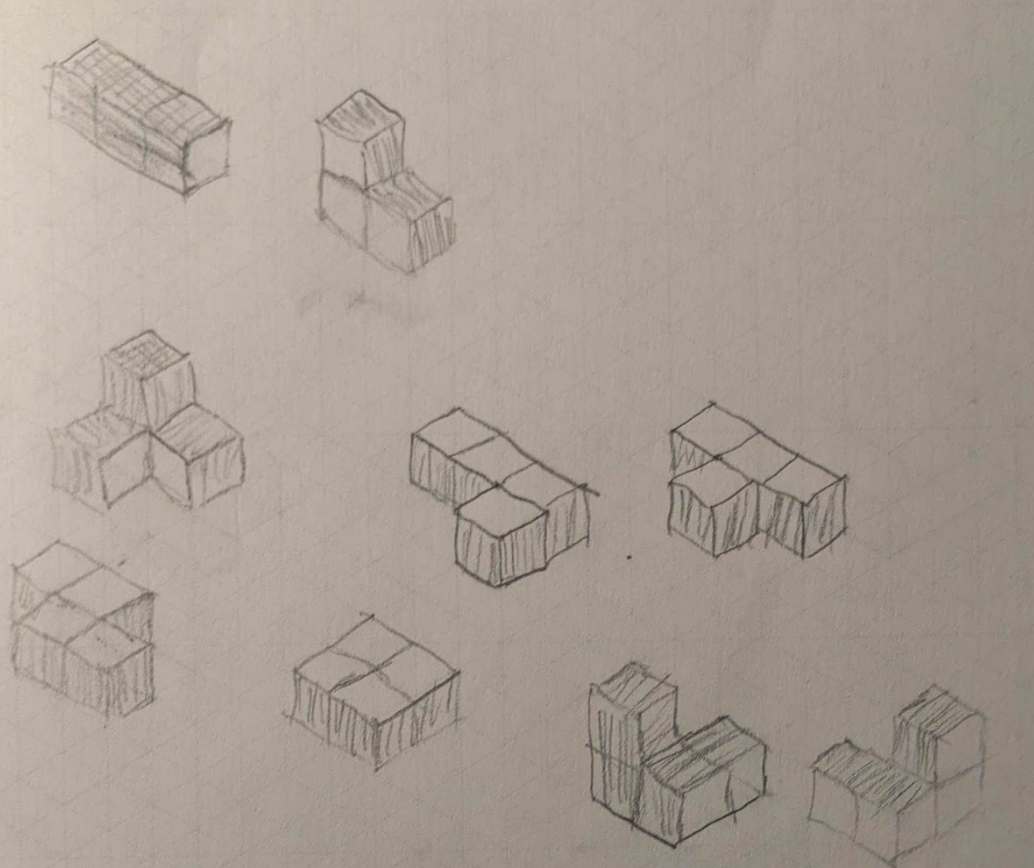

Above are the possibilities for n=3 and n=4

Above are the possibilities for n=3 and n=4

Attempts at an Explicit Solution

The puzzle parts built out of wood cubes are actually known in mathematics as “polycubes”, which are fully connected solids made by combining unit cubes. Counting the number of possible polycubes composed of n cubes is called “polycube enumeration”.

The first thing I tried after hand-drawing a few possibilities was building a recursive formula. I figured that each extra cube added would multiply the number of possiblities by the number of faces of the polycube. For example, a polycube of n=1 has 1 possibility and 6 faces, so n=2 has 6 possibilities (not accounting for uniqueness yet). I could then divide by the number of possible orientations (6), to obtain my total. My idea was kind of inspired by mathematical induction, where the base case is the trivial n=1, and every increasing n builds off the previous set of polycubes. Unfortunately, this approach doesn’t work because not all orientations are guaranteed to be generated (although all unique polycubes are), so we don’t know what to divide by.

Chirality

This is somewhat irrelevant, but it’s something kind of cool I learned about. Think of your right and left hands - they have the same shape as each other, but they’re mirror images. There’s no way to overlap your hands with both palms facing the same direction (when you clap, your fingers overlap but are facing opposite directions). This idea also applies for polycubes. Consider the last 2 polycubes in my somewhat-messy hand-drawn chart above: they’re almost the same, but they’re distinct. This is called a chiral pair. (Sometimes, we want to treat chiral pairs as non-distinct, but I’ll treat them as distinct in my project.)

Back to Finding an Explicit Solution

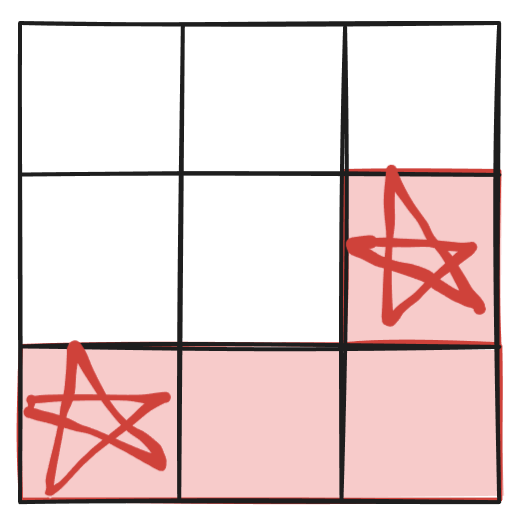

My next idea was to define a polycube by its endpoints. To simplify my explanation, let’s take 2d polycubes (combinations of unit squares, known as polyominoes) as an example.

The red polyomino is a path from the first red star to the second red star. The really nice thing about this approach is that it allows us to take advantage of a nice trick from competition math: the number of possible paths of length n (excluding the starting point) going up k squares between points a and b is (n Choose k). In the example above, the path length is 3 steps (excluding the starting point) and point b is 1 square abouve point a, so there are (3 Choose 1) = 3 ways of going between the two red stars. This method of choosing end points to define polycubes also works in 3D space, and takes the form (n Choose j)*(n Choose k). When we take all possible endpoints within some distance of the starting point, we can ennumerate all unique polycubes with this trick. Unfortunately, this again doesn’t guarantee that all the polycubes are unique. I was planning on continuing to work in this direction, but I googled the problem and it turns out: polycube enumeration is an unsolved problem in mathematics. I assumed this direction had been adequately explored by tons of mathematicians before me, so I decided to solve the problem computationally instead.

Solving the Problem with Computers

The teacher told the class that we’d get full credit as long as we made a reasonable attempt at n=5 and n=6. I could have taken the easy way out and estimated both, but I was already too deep in the hole by this point.

The nice thing about computers is that they can eliminate the need to find some clever mathematical way of eliminating duplicates. Instead, I can use either of the approaches I described earlier, and check for duplicates with something like a hashtable.

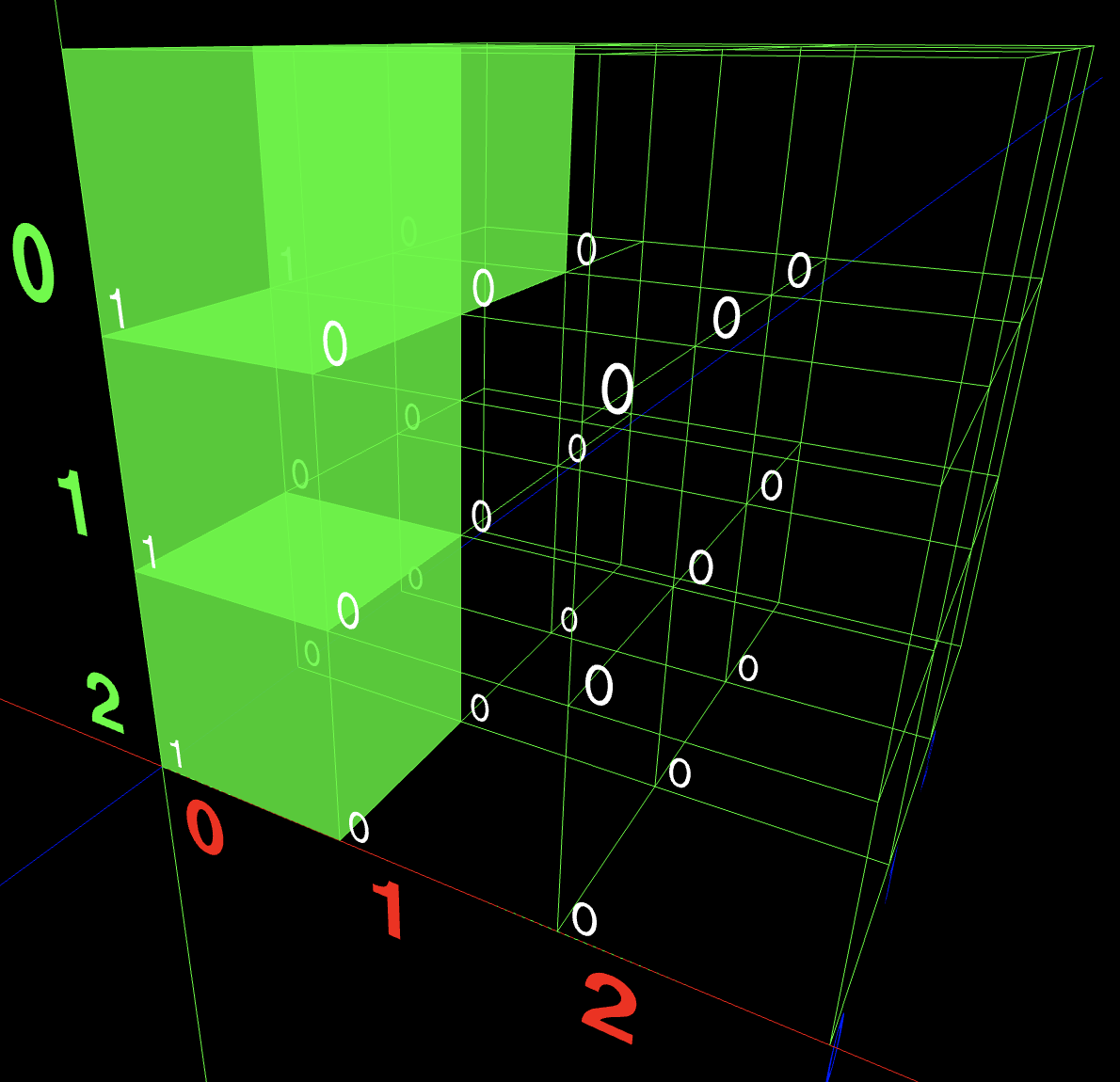

I started with representing polycubes in a numpy array of dimension DxDxD, where a 1 means a cube exists in that slot.

Above is a representation of a “L” piece in a numpy array.

I really liked this approach because it allows me to compute all orthogonal orientations quickly by simply traversing the matrix along different axes in different directions. For example, to flip the piece upside down, I would simply start traversing the matrix bottom to top. To rotate it 90 degrees, I might traverse it along the x-axis instead of the z-axis (this is also why there are only 6 orthogonal orientations of a polycube: they correspond to the 6 faces of a cube, or alternatively, because there are 3 axes and 2 directions to traverse each axis (negative to positive and positive to negative), the 3x2=6 ways of traversing the matrix).

Unfortunately, this approach is really, really memory inefficient, because every polycube of n cubes has to be represented by a nxnxn matrix, which wastes a lot of space.

Instead, I decided to simply represent each polycube with a list of the coordinates of cubes it contains. For example, a L shaped cube might be represented as [(0, 0, 0), (0, 0, 1), (0, 0, 2), (1, 0, 2)]. To compute the orthogonal orientations of such a representation, I noticed that rotations are equivalent to compositions of reflections, so I just compiled a list of lambda functions that correspond to each of the 6 rotations.

Now, to enumerate all polycubes composed of n cubes, I start with enumerating all polycubes composed of 1 cube (which is just 1 cube). The program then enumerates all all unique polycubes (though not necessarily in every orientation) composed of 2 cubes with a breadth-first-search approach by adding a cube in every possible location (just like induction). For each polycube, all 6 orientations are computed. Naively, we could compute a hash for all 6 orientations, and compare future polycubes with all 6 to check for duplicates. However, this requres 36x more computation than necessary. Instead, we compute a singular “canonical form” of a polycube, which is the polycube where the lowest cube is at (0, 0, 0), and the list is sorted in lexicographical order. Then, only this canonical form is added to the duplicate-checking set, and only the canonical form is used to check for duplicates. Because the way of computing the canonical form is standardized for all polycubes, checking for duplicates this way is perfectly legitimate.

With this program, I can enumerate all polycubes up to and including n=8. Unfortunately, this problem gets exponentially harder as n increases. I know that researchers have enumerated polycubes up to n=22 (using lots of fancy math and CS terms I didn’t understand), but it seems like most implementations by casuals like me get to somewhere from the n=7 to n=9 range, so I’m reasonably happy with the performance. Overall, this was a very simple project that only took a day, but I do think the difficulty in such an easy seeming problem is interesting.

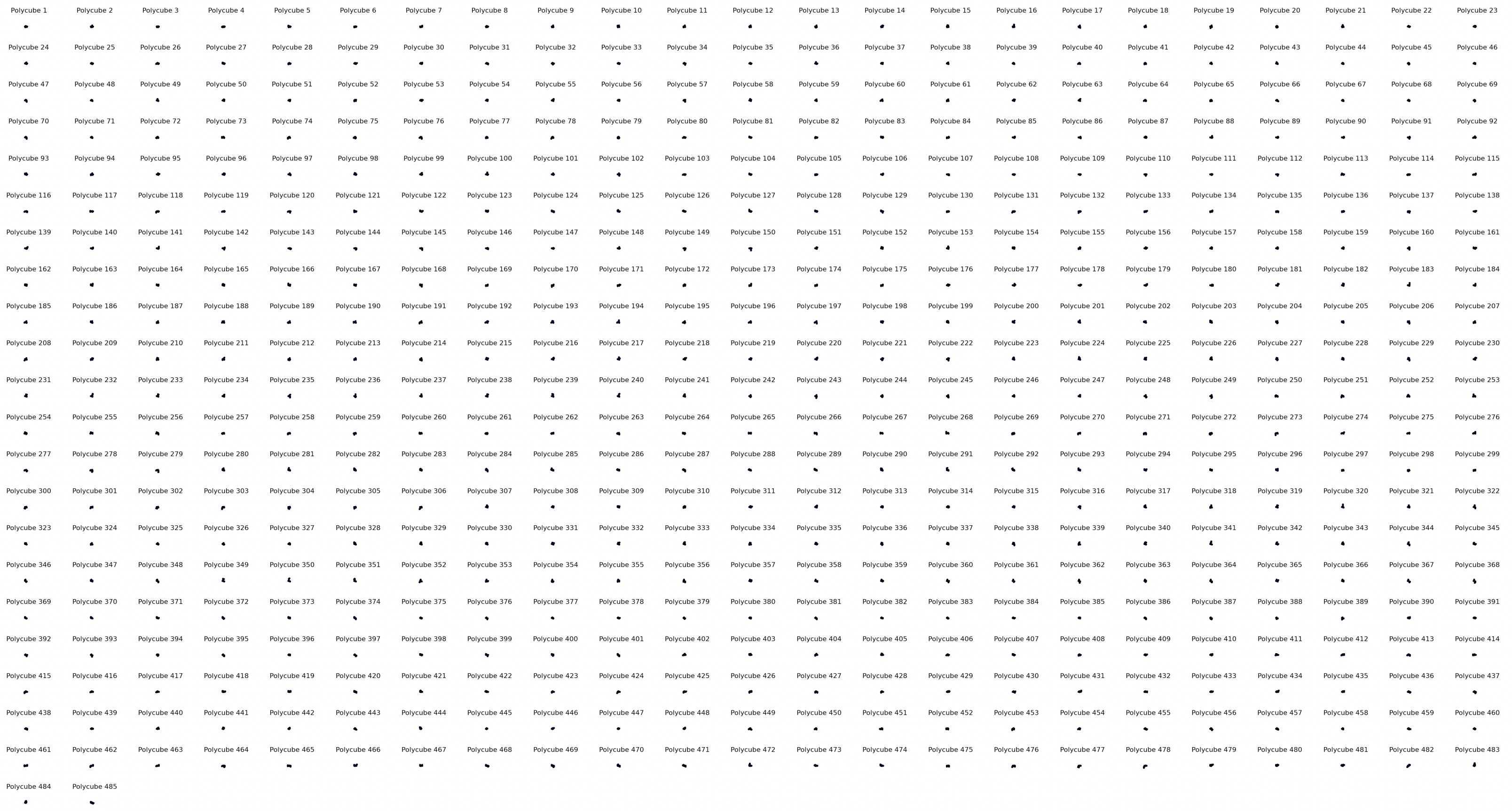

I also learned how to use matplotlib’s 3D visualization tools: for fun, here’s all the possible polycubes for n=5, 6, and 7 (n=8 wouldn’t fit onto my screen, but I did find all 6922 possibilities.)

n=5

n=6

n=7

You can find the code for this project here: https://github.com/NinjadenMu/polycubes