Roman Tic-Tac-Toe (Rota) AI

The inspiration for this project

I was walking to lunch today when I passed the Latin classroom, and impulsively, I decided to take a look at the Latin club meeting that was going on. I had taken 4 years of Latin, ending last year - it wasn’t an easy class, but I did enjoy it overall and intend to take one more year in my senior year. The Latin club was hosting a Roman Tic-Tac-Toe competition, which I managed to win. I got a really cool scorpion made of pipe cleaners as a prize, but more importantly, was introduced to a pretty interesting game.

Meet my pipe cleaner scorpion Garry. This is the first time Garry’s gotten fed since I won him, so he’s a bit thin right now.

Meet my pipe cleaner scorpion Garry. This is the first time Garry’s gotten fed since I won him, so he’s a bit thin right now.

The rules of Roman Tic Tac Toe (Rota)

Roman Tic Tac Toe, also known as Rota, is a fairly simple strategy game played on a ciruclar board. Its original Latin name was probably “Terni Lapilli” (3 stones). Rota is not the most difficult game, but it’s also not easy to play and a good bit harder than Tic-Tac-Toe.

2 players are given 3 tokens to start. Players take turns placing tokens on open spots (empty circles), until both players have placed 3 tokens. Once all tokens are placed, players take turns moving a token along one of the edges (the perimeter of the large circle or the spokes). Players can only slide a token across one edge (can only go to directly connected spots), and may not jump over or land on occupied spots. Players also may not skip a turn. To win, a player must have occupied 3 colinear spots, one of which must be the center spot.

You can find the list of rules and a printable board here

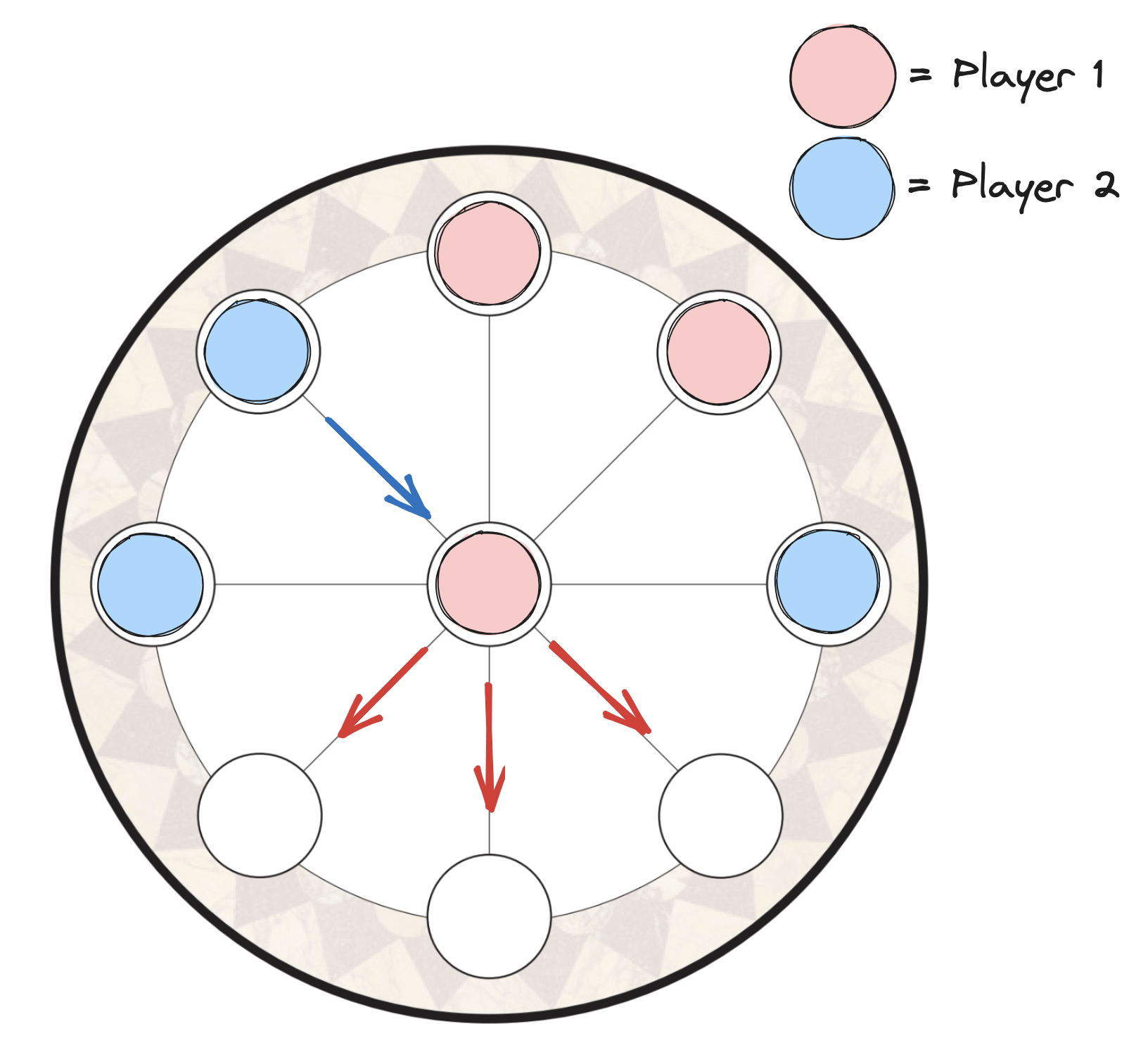

When I first learned the rules, I thought the game was pretty trivial and boring. After all, if you need to occupy the center spot to win and the player taking the first turn can place their token into the center spot, how could the player taking the second turn ever win? It turns out that there is a bit of strategy needed - the second player can trap 2 of the first player’s pieces, so the first player is forced to move out of the center spot with their third piece. This concept is called “zugzwang” in chess - a player may have no option but to make a move that loses.

Take the example below: if it’s red’s turn, red is forced to slide their token in the center spot out, since their other 2 tokens are trapped. Blue, who took the center spot and didn’t get to claim the center spot, now has the opportunity to slide into the center spot on the next turn and win.

For red to avoid such a situation, they have to plan ahead, making sure that their pieces always have space to maneuver. This can be done by playing sequences of moves that essentially “waste” a turn, or by strategically giving up the center spot at a time that doesn’t result in a loss. This is quite similar to a chess endgame concept called “triangulation”, which really confused me when I was studying chess.

Implementing the game representation (the slow way)

To build an AI that can play Rota, we need to use some kind of search algorithm that will find the sequence of moves that will lead to the optimal outcome. The search algorithm will build some sort of tree, in which each node represents a board state that can be reached from its parent node (this parent node could be just a possibility from its own parent node).

The search algorithm needs an accurate representation of the game, which is basically an object which stores a game state, and has functions that can return the legal moves in that game state and whether a side has won. This representation should be able to know when a side has won the game (so the search algorithm can stop searching), and all the possible/legal moves in a given position (so the search algorithm can know which moves to add to its search tree.)

The way we represent the game is crucial because we need it to not only be accurate, but fast. Our search algorithm can search deeper in the same amount of times if we can generate all the possible moves from a given node faster.

I just wanted to give a quick primer on search trees to explain why the game representation is important first. I’ll elaborate more on search algorithms later in this post, but you can watch this video by Sebastian Lague explaining one search algorithm, minimax, first, if you want. Link

Representing the rules of Rota

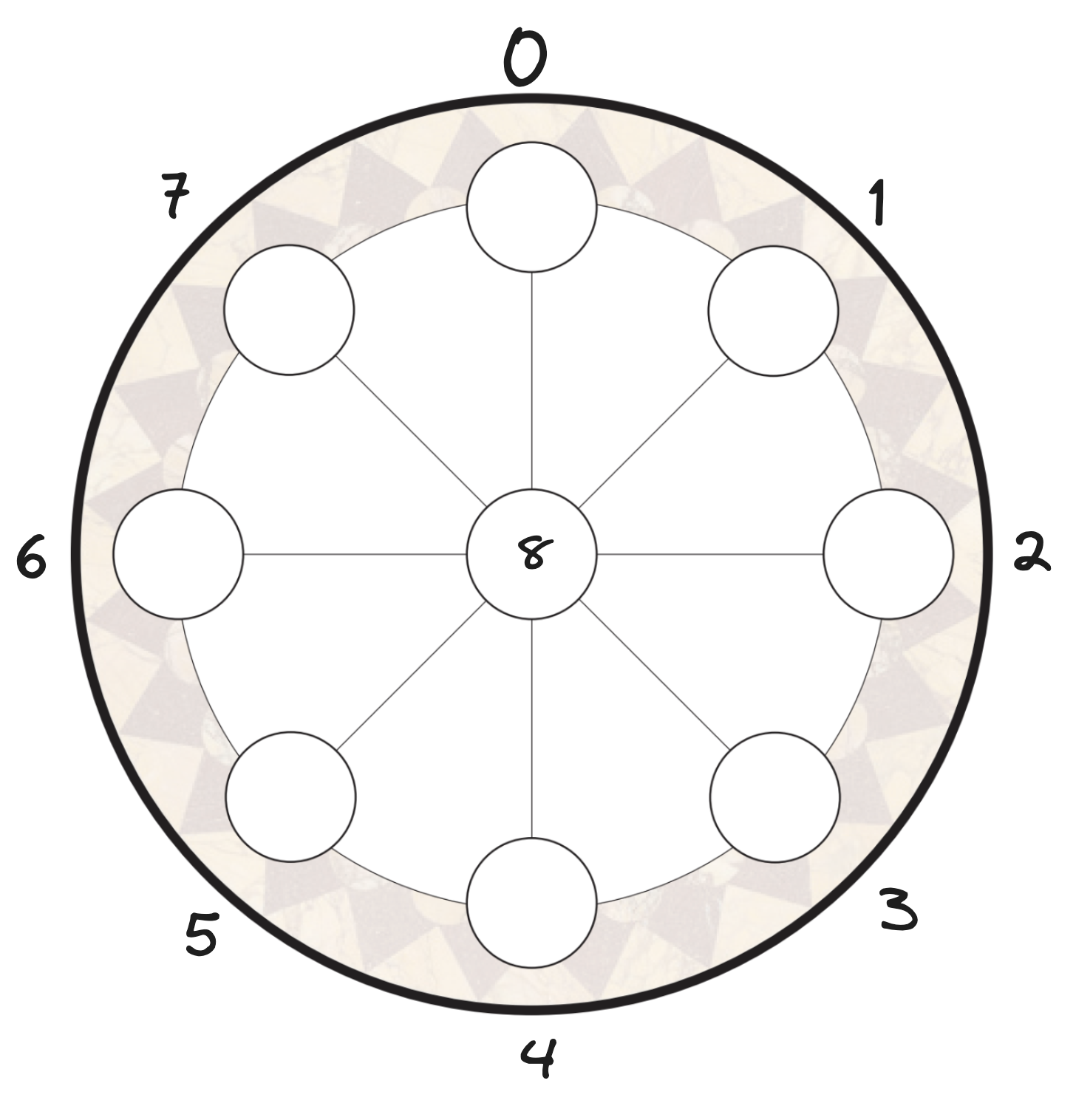

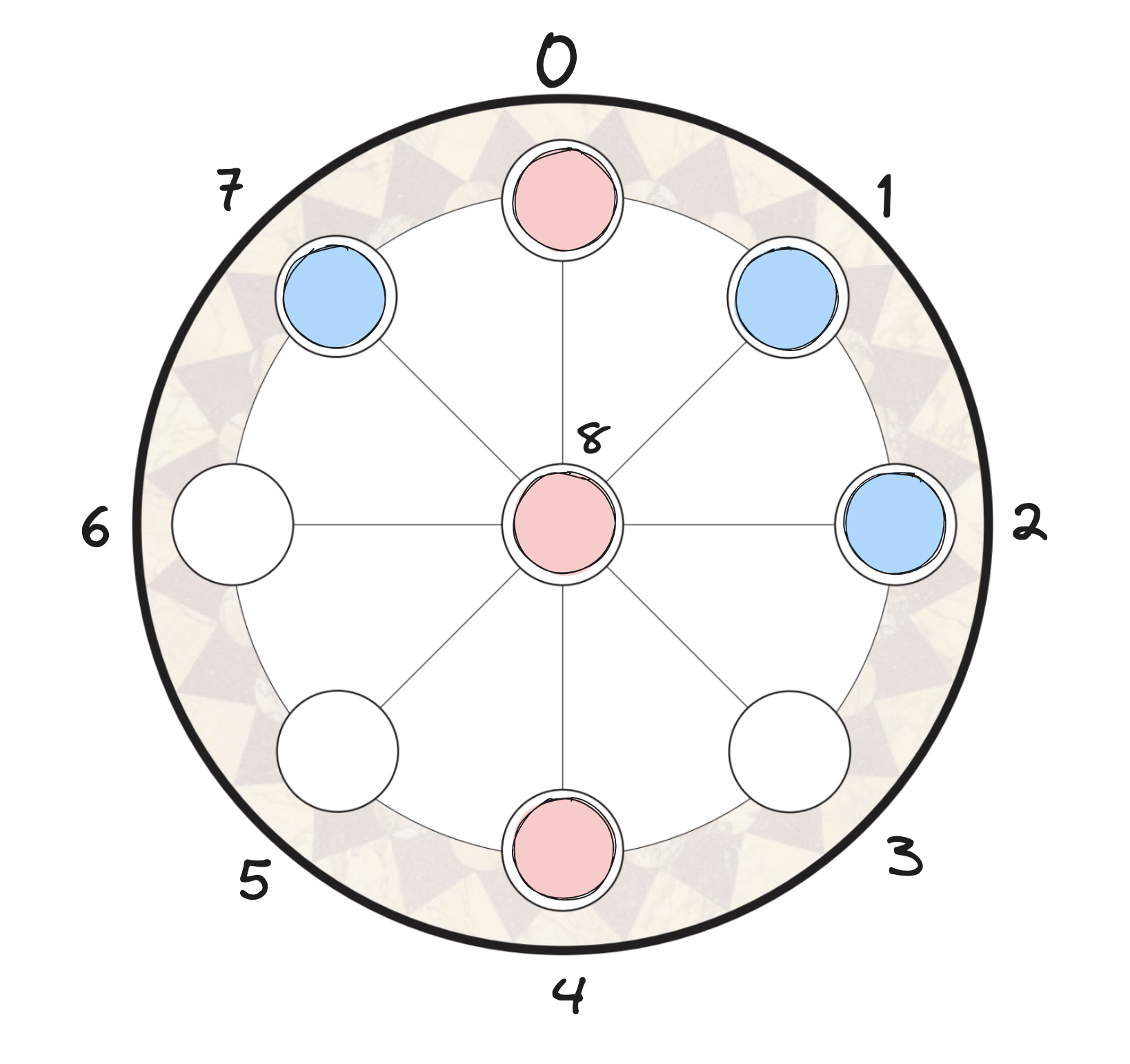

A Rota board is really just a graph - pieces can move from cell to cell based on specific paths. The outside spots are numbered clockwise from 0-7, while the center spot is 8.

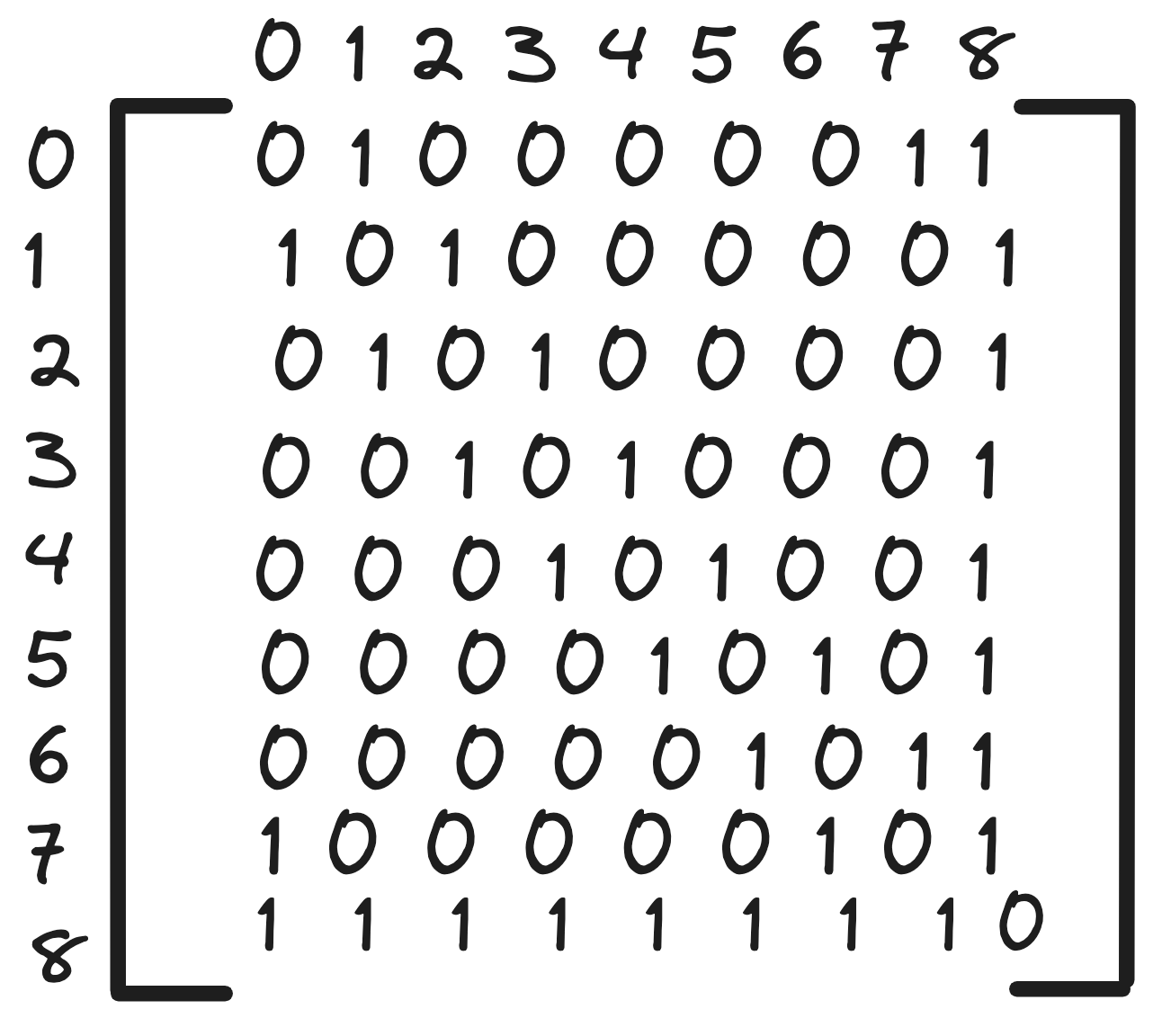

Therefore, we can get all the possible piece movements using an adjacency matrix. Since you can only move one spot per turn, the adjacency matrix looks something like this:

A 1 in a cell tells us that a token in slot {row #} can slide to slot {column #}. For example, every cell in row 8 except (row 8, column 8) is a 1 since the 8th spot is the center spot and can travel to any other spot besides itself. In contrast, in row 0, only the cells in columns 1, 7, 8 are 1s because slot 0 can either slide clockwise to slot 1 or counterclockwise to slot 7, or go to the center, at slot 8.

Representing the board position and Getting all Legal Moves

We also have to be able to be able to know where each piece is. To do this, we can simply use 6 integers from -1 to 8, each corresponding to the spot a piece is on (there are 6 pieces, 3 for each player). -1 will represent a piece that has not yet been placed, while 0-8 represent a spot.

For example, the board

| would be represented by {Red Pieces on: 0, 8, 4 | Blue pieces on: 7, 1, 2} (Recall Red = Player 1, Blue = Player 2). |

To get the legal moves from where the pieces are, we can simply look up the places the 3 pieces of the player-to-move can move to by indexing the adjacency matrix with the integer corresponding to each spot (we don’t care about the other player’s pieces since only one player can move a piece per turn). This will return a 9 element list, in which each entry corresponds to whether a piece can slide to the spot represented by that entry. By looping from 0-8, and checking whether the i-th element of the 9 element list is 1 or 0, and that the i-th spot is not already occupied by a piece, we can find the new integer(s) that a piece will correspond to after sliding in one of the possible directions.

In the example above, one set of possible moves comes from moving Red’s piece on spot 8. We first index the adjacency matrix at row = 8 to get the list [1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0]. Then, we loop through that list. If list[i] == 1, we then check if i is already occupied by another piece. For example, even though list[2] == 1, moving the piece on 8 -> 2 would not be legal since Blue has a piece on 2. If the i-th spot is unoccupied, 8->i is a legal move. To generate every possible move, we repeat the above process for the 3 pieces of the player to move. Additionally, if any pieces are -1, we can say that piece can “go” to any unoccupied spot, which we’ll find using a similar loop (but skipping checking the adjacency matrix).

Checking who won

To check who won, I first sorted the pieces of each player by the number of its spot. For example, the board represented by {Red Pieces on: 0, 8, 4 | Blue pieces on: 7, 1, 2} would be rearranged to {Red Pieces on: 0, 4, 8 | Blue Pieces on: 1, 2, 7}. This lets us immediately check if the last value of each player’s pieces is 8, and if the first value is -1. Since a player can only win if one of their pieces is on 8 (remember you have to have 3 in a row going through the center), we can stop checking and return “game ongoing” if spot 8 is unoccupied. Similarily, if a player has a piece with value -1, then they have less than 3 pieces on the board and cannot possibly have 3 in a row, so we can stop checking and return “game ongoing”. If it is occupied, we only have to check for a win by the player with an 8 (in this case, Red). I then check if Red (or Blue if they have an 8) has 3 pieces in a row by checking if their combination of pieces is in a hardcoded list of winning combinations. This list is actually not that big, since we only have to account for ascending order after the sorting step. The winning combinations are: [{0, 4, 8}, {1, 5, 8}, {2, 6, 8}, {3, 7, 8}]

Implementing the game representation (the fast way)

As I said earlier, we want our game representation to be able to generate the legal moves and check for a win quickly so we can search deeper in less time. To do this, we’ll use bitboards.

I’ll explain this later since I don’t feel like writing this part rn