Relativistic Space Invaders: Special Relativity and How to Render its Effects

Why Special Relativity was Formulated

Almost all of our everyday experience involves objects with velocities significantly less than that of light. Newtonian physics was based on the observation of these slow objects, and therefore fails to model the motion of objects at speeds near the speed of light. Regarding his special relativity theory, Einstein wrote: “The relativity theory arose from necessity, from serious and deep contradictions in the old theory from which there seemed no escape. The strength of the new theory lies in the consistency and simplicity with which it solves all these difficulties.” As the velocities of objects approach 0, Einstein’s theory approaches the results given by Newtonian physics - however, Einstein’s theories were also consistent with observations of objects at velocities near the speed of light.

Before Special Relativity - Galilean Relativity

Frames of Reference

A frame of reference must be established to describe the motion of an object. Frames of reference are the coordinate systems that define the positions of objects from the perspective of an observer. The most basic forms of special relativity and Galilean relativity deal only with inertial frames of reference, which do not accelerate (relative to other inertial frames of reference) - special relativity paired with more advanced math and general relativity can deal with accelerating frames of reference.

Galilean Invariance

Galilean invariance claims that the fundamental laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames of reference. This is the basis of all of Galilean relativity.

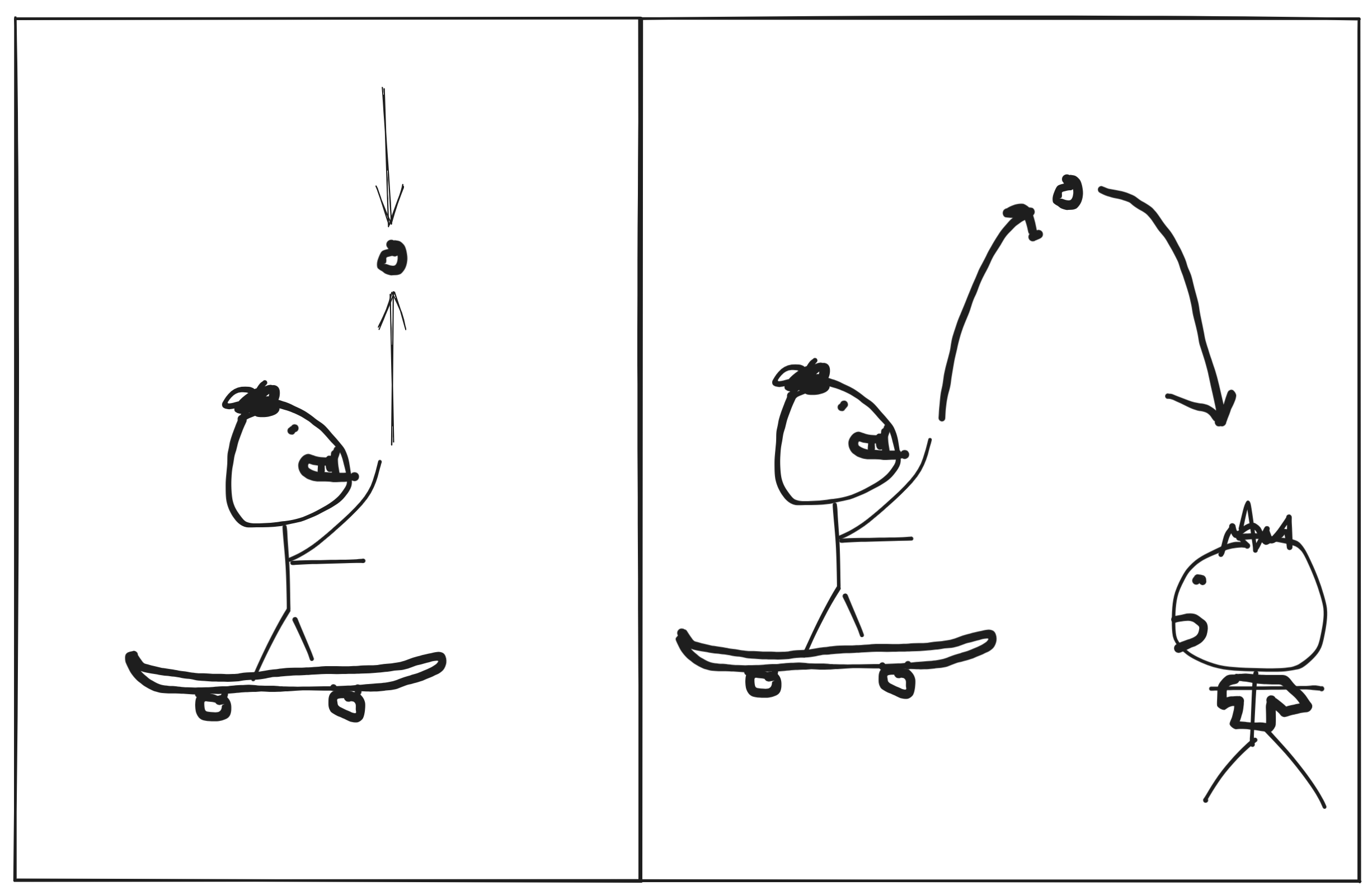

Take a skateboarder throwing a ball upwards as an example:

The skateboard moves to the right with a velocity v relative to the ground. The observer on the skateboard throws the ball straight up and sees the ball following a straight line. The observer standing on the ground sees something completely different - for him, the ball appears to moving alogn a parabola. However, they both agree that the ball can be modeled as an object under constant acceleration g due to the laws of universal gravitation. In other words, the ball is governed by the same laws of physics in both reference forms. Therefore, because all other factors have the same influence on the ball, the only cause for the different observations is the relative motion between the 2 frames of reference - indeed, the vertical component of the ball’s motion is the same from both frames of reference.

Galilean Space-time Transformation Equations

Because different observations from different inertial frames of reference occur only due to the relative velocity between frames (following from Galilean invariance), the Galilean space-time transformation equations seek to convert observations from one reference frame to the observations from another. In addition to Galilean invariance, the equations also use Newton’s axioms in their derivation - primarily that all inertial references share an universal time (events occur at the same time in any 2 frames). The Galilean transformation equations will be shown and derived below:

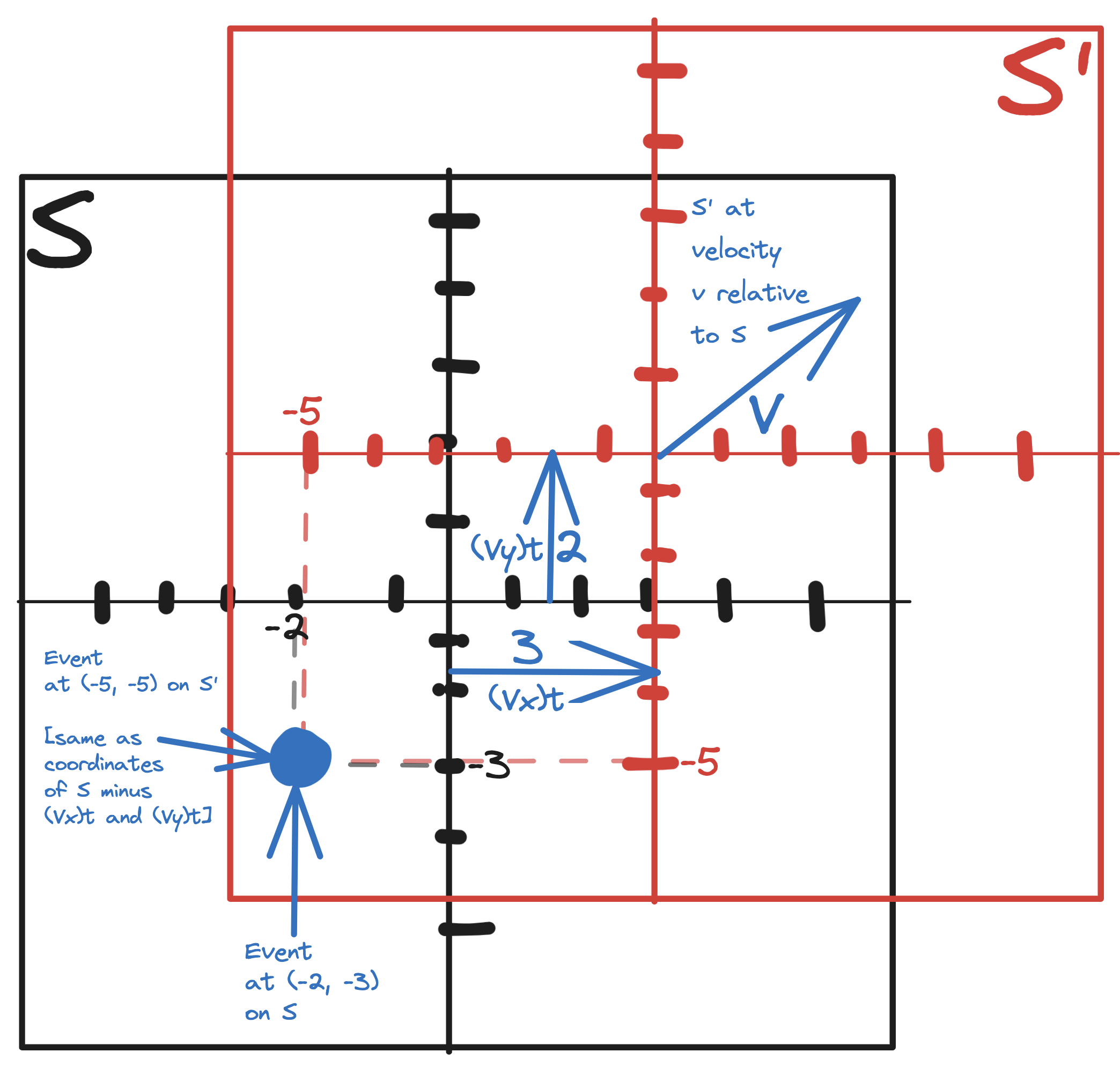

Take two inertial reference frames S and S’, where S’ has velocity v relative to S and has the same position as S at time ti. An object observed in frame S will have position (x, y, z) at time t. The same object observed from S’ will have position (x’, y’, z’) at time t’. From Newton’s axioms, we know that t’=t. At time t, S’ is at a distance of vt from S, where v has components vx, vy, and vz. Therefore, the coordinate system of S’ is offset from that of S by (vxt, vyt, and vzt). There is no confusion over whether the offset is vt or vt’ because t’=t.

Following from this,

x’ = x - vxt,

y’ = y - vyt,

z’ = z - vzt,

t’=t.

Observe how in the diagram, as the red coordinate system (S’) moves away from the black coordinate system (S) at velocity v, the object’s coordinates are defined as (x’, y’) = (x - vxt, y - vyt)

These equations also tell us that all objects appear to have the same dimensions regardless of the frame of reference: imagine an ant crawling along an object at velocity u takes time Δt to go from one end of the object to the other. The difference in the coordinates of the end and start positions of the ant is the length of the object and can be calculated using the equation end position = start position + uΔt. When the positions are converted from their coordinates in one reference frame to the coordinates in another reference frame using the transformation equations, the difference remains the same because the offsets vt for both the end and the start cancel out.

Galilean Velocity Transformation Equations

The space-time transformation equations also allow us to calculate the observed velocities of objects from different reference frames by taking the derivative of the position of an object with respect to time. For example, dx/dt = dx’/dt - v. Therefore, the observed velocity u’ of an object from one reference frame can be defined as u’ = u - v.